It is a time of despondency and the desire for death. Man cannot and does not survive in this cruel zone. This means that all lived reality is already so destitute that it reveals itself transfigured, veiled or enriched in proportion to the strength of our capacity for passion and dream.

René Ménil

Our Miraculous Hearts

Phoebe Boswell is a portrait painter and multidisciplinary artist who creates portals that return us to the tender magnificence of our miraculous hearts.

Phoebe Boswell, Love’s Promise to the Weather, 2024, and Phoebe Boswell photographed by Adenike Oke.

‘I’m reflecting on the first question you asked—how’s your heart?—and it’s strange to think about it because it’s tested me so much, and in many ways it’s fragile. I know now because of what’s happened to it, it’s going to be fragile forever. But at the same time, it’s absolutely not. Your heart can do miraculous things’.

PHOEBE BOSWELL

If courage had a colour, it would be Boswell Blue. A tender meditation on grief, healing and courage, with an artist who creates portals that return us to our miraculous hearts.

Our Miraculous Hearts with Phoebe Boswell is available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Busy Being Black listeners are invited to Queeriosities (26–28 September) in Peckham, London. Use the code busybeingblack10 for a discount on opening night tickets.

Josh Rivers:

Phoebe Boswell, I cannot tell you how delighted, honoured, thrilled, enthused I am to have you here. Thank you so much for accepting this invitation to Busy Being Black.

Phoebe Boswell:

Thank you for having me. I feel like it's a long time coming. I think we spoke first about doing this a few years ago, no?

JOSH:

Yes, you had reached out to me to lend my voice to and participate in the wonderful work that you were doing in New Orleans, Do We Muse on the Sky or Remember the Sea, which I was so honoured to be a part of. Thank you. But you know what? I'm learning everything in its time. Everything happens when it's supposed to.

PHOEBE:

Exactly.

JOSH:

As you know, to open all of my conversations on the show, I ask all of my guests the same question. How's your heart?

PHOEBE:

It's good. It is robust and healing. And, yeah, it's treated me well, I think.

JOSH:

I ask you this question—and it's not by rote, right? It's a very intentional way to open these conversations—but I understand that question might also land quite differently for you as well. And we'll get to that, I think. So I first encountered you and your work at Autograph in 2019, with The Space Between Things, and I was stunned. I was blown away by your vulnerability and the sheer diversity of mediums you employed to express the journey you were on at the time, and that you may actually still be on. So I first want to thank you for your artistic and emotional generosity. The Space Between Things seems to me like it took a tremendous amount of courage. Did you feel courageous at the time?

PHOEBE:

I don't think I felt courageous. I felt like art was something that changed meaning for me. It became a safety mechanism, or it became like a life jacket in a way. And I don't think I was thinking about it as courageous. I think I was just seeing it as a way through. I kind of thought it was self-indulgent to begin with, to be honest. I thought that it was helping me, but it wasn't necessarily for anyone else or to be seen by anyone else. I'd had a very bad accident. And it had caused a whole number of problems, including losing sight in my right eye, and the stress of it all made my heart rupture. So, I went into a very bleak place, as you might imagine. Going to the studio became a way through, and it became something that was kind of aside from anything I'd thought about art previously, about what it does externally, and it became a completely internal conversation. I think it definitely gave me courage, but I don't think that's how I was processing it at the time.

JOSH:

You know, it's just now occurring to me, I'm in my memory walking through the exhibition for the first time, and I believe that within The Space Between Things, there is footage from the surgeries that your doctor performed on your eye and that he contributed, if you will, to this exploration. And I believe those were in the upstairs gallery, right? It was quite dark, and downstairs, around the walls, these beautiful illustrations of you in all these different forms and shapes. And there was nothing, to my mind at the time, bleak about it. It was curious. It was inquisitive. And maybe that says a lot about me as the viewer, right? And so to be returning to The Space Between Things now, all these years later, and to re-engage with this work again, I feel it more. I do feel a kind of, maybe even a grasping, right? If I can put all of this stuff in front of me, I might be able to make more sense of it. Has your relationship to The Space Between Things evolved since that time?

PHOEBE:

First, I'd be really interested to know from you why you think it reaches you differently now. But for me, it was a very meaningful and cathartic work at the time, and a lot of decisions were made in that work to leave it there. It was a 27-metre-long drawing. I would take a photo of myself every morning in whatever state I was in, naked, and I would draw that onto the wall. And it was in willow charcoal because it's so soft and it's so delicate and it can be damaged or blown away very easily or rubbed away very easily. I wanted there to be this sense that I'm putting this here and I'm making a bid to trust you to protect it and protect me and to hold me in it, which was something that I was struggling with after this thing that happened physically to me. And then the other decision to make it on the wall so that it would have to be removed—it wouldn't last. I didn't want this to be something that then became something I put in storage, or I had to think about how to sell. It wasn't that work, and so I kind of left it there, and I really mean that—like the intention was to leave it in the space and to leave this story in the space.

I was really grateful to Autograph and to Renée Mussai, who was the curator, for giving me that space and for giving me the time. They gave me 21 days to do this thing, even though we didn't know what it was going to be at the end. And then it kind of took on a life of its own as a lot of art does. I think it reached people. I think it gave people who came into that space some kind of maybe freedom to also feel their feelings and to kind of work through something to do with grief or something to do with trauma. And so it gave me a lot, that show. It gave me a lot of hope, and it gave me a lot of re-trusting in the things that I'd stopped trusting. And I have really fond memories of hearing people's responses to it. It really did save me from a really difficult time. So I'll always be really indebted to it.

On the Line, Phoebe Boswell, 2019. Willow charcoal on wall, Autograph ABP, Shoreditch. Intentionally impermanent. Photograph by Josh Rivers (24 January 2019).

JOSH:

The Space Between Things lands differently with me, or I orient myself differently to it because in 2019, I had my full armour on. It was impenetrable at that stage, and I was only two years out of—less than two years out of—the tremendously painful takedown and public shaming. I wasn't accessing myself fully at that time, and I was really, really focused on being beyond reproach, beyond critique. And so I think there was a lot that I engaged with at that time that I engaged with quite surface level, particularly if it had anything to do with grief or pain or—I was like, this is a thing to be observed only. Now I'm coming to The Space Between Things and indeed art in general, raw, open, ready. I want to be touched, transformed, moved around, startled. Five years later, I come to your work much more honestly.

PHOEBE:

I love that. I'm glad for that. I think for me, art is a place where I can be very vulnerable in ways that, still now, I struggle with in reality. I think it always has been, but that moment was a real pivotal and defining moment for me to know what art is and what it does for me. I think even now it's where I feel like I can be as soft and raw and open, but I think trauma does things to you that are non-linear; and with all the best intentions and all the will in the world to want to learn from the lesson, learn from the pain, you still find yourself putting walls up and being afraid and being untrusting, but love requires you to be trusting. So, art is that place for me, and I'm always really moved when I hear that it offers that place to anyone else.

JOSH:

Is there an artist who does that for you, or who has always done that for you, whose work cracks you open?

PHOEBE:

That is impossible. There are too many, honestly. I would say an artist who always has the ability to open me up, but also to kind of embrace and caress me is Dineo Seshee Bopape. She works with the land, and she works with soil and she makes these really felt spaces that require you to be open and to be soft. I think Paula Rego's pastels always have a way to kind of rip me open.

JOSH:

Mine's El Greco. I first saw his work in 2014 or 2015 at the Prado in Madrid. I had spent a couple of hours in there, and when I came across El Greco, I was like, ‘Oh my God, who is this guy?’ And every time I go back to Madrid, I go see El Greco at the Prado. And for years, I haven't been able to explain why I'm seeing myself reflected back to me—and this year I could finally name it: it is the way El Greco's paintings reveal that morbidity and vitality live together. You cannot separate them. And it's the storminess of the backgrounds and the vibrancy of the colours. You don't have one that's only vibrant and one that's only dark; they're always together. It's a reflection of how I feel inside, right? There's such a luminescence inside, and there is also—to maybe use a Boswellian example—a very stormy seascape.

Detail of Manifesto (for a Lost Cause), Paula Rego, 1965. Collection: Tate Britain.

Detail of The Adoration of the Shepherds, El Greco, c. 1614. Collection: Museo del Prado.

For Our Soals Soared There, Phoebe Boswell, 2018. Willow charcoal on wall, Autograph ABP, Shoreditch. Intentionally impermanent.

PHOEBE:

I actually had a really surprising response recently to Rothko, who everyone says, ‘Rothko! When I stand in front of Rothko …’ and I have never felt that ever. I've never understood that. But I went to see the show in Paris, and it was a retrospective. I didn't know that he was figurative before—like his early works are all figurative. And then there was the war, and artists were trying to figure out how to do figuration after seeing so much violence, which I think is a moment that we're also in now. Guernica was made, and all of these really important artworks were created. And his figurative work before was—I mean, it was solid. It was good. And then he had this moment of rupture. And then everything figuratively—it all kind of started falling apart. He started doing these allegorical works, which kind of didn't—I don't know, they were less convincing, I guess. And then you saw the moment where it all just fell apart completely and the figure was dissolved into what became what we now know to be ‘Rothko’.

I've always thought about what abstraction means and whether there is a kind of liberation in abstraction. When you're walking in the world with subjectivities that are seldom seen fully or seen without nuance or care, I've often wondered about whether removing the figure and removing that conversation would be some kind of liberating moment. And when I then stood in front of the Rothko that we know, I felt a really strong sensation of like when the human reaches the end of their rope and they break and they falter and it all dissolves—like anything to do with meaning or language dissolves into something else and then the spirit comes out and now I kind of feel them more. But I was very surprised by that moment because I wasn't expecting it at all.

JOSH:

The big lesson for me about art—well, I think there's a very intellectual way of engaging with art. We learn a lot from John Berger's way of seeing and, you know, we apply our intellectual, educated brain to understand where the artist was and who he was, blah, blah, blah. And then there's the underworld of our emotions that art reveals to us and that sometimes we cannot explain—and that are perhaps not even meant to be explained. And maybe that's the power in abstraction as well, is that like, I don't know why that wall of colour does what it does, but it is me. That is how I feel.

The images which arise out of the depths link us to that throbbing, insistent hum which is the sound of the eternal. As children, we listened to the sound of the sea still echoing in the shell we picked up by the shore. That ancestral roar links us to the great sea which surges within us as well.

James Hollis

JOSH:

I'm going to bring you very gently back to The Space Between Things before we move on. One of the elements about The Space Between Things that really resonates with me is this non-spoken conversation about grief between you and your father that people wouldn't really know unless they had a conversation with you about how you managed to capture these beautiful visuals of you floating in this huge body of water. So I wonder if you can talk to listeners a little bit about this element of the exhibition and how you brought your father into a conversation about grief with you through this art-making practice.

Still from Ythlaf, Phoebe Boswell, 2018.

PHOEBE:

So it really struck me how ill-equipped I was and we were to deal with the magnitude of what had happened, and how culturally, growing up in the west, the language around healing is ‘grin and bear it’, ‘suck it up’, ‘you're so brave if you don't show how much this is affecting you’. And not for any fault of my parents, but I grew up with the understanding that it's really brave to act as much as possible to an outside eye as if you are not being completely heartbroken by what's happened to you. And because my heart physically broke from this moment, there was no way of doing that because everything was a testimony to the fact that I was in a lot of deep pain. But that was really uncomfortable for me and for everyone involved. And I think I was kind of ashamed to be weak in this moment. And obviously, I could see that my dad was struggling to contain his own grief seeing his daughter in this bad situation. And we couldn't talk about it.

I decided to do this work when I was in the heart hospital. The woman next to me was in a lot of pain, very delirious. And she kept saying, ‘Take me to the lighthouse, take me to the lighthouse’. So that's where this imagery around the sea came from because I was lying in bed with this broken eye and this broken heart, and I was thinking, ‘Where is my lighthouse and who can be my lighthouse and can I be my lighthouse?’ So doing this with my dad was a way for us, as you said, to be inside this grief without having to say it. I was offered therapy because of the physical trauma of what happened, and it was the first time I did therapy. I never thought I wanted to do therapy—at the beginning, I was like, ‘I don't need it, I’m totally fine’. It was a huge gift because it opened me up to understand a lot of things. In a lot of ways, it was mutually therapeutic. So I think I understand my dad better, and I think I express myself perhaps better now. I don't know. I think it's hard to talk about parents in this public way that doesn't—you know, yeah…

JOSH:

Sure. To not be specific to your experience or your relationship with your parents, what I really loved about this gesture was this invitation to ‘stand beside me in a way that you might know how.’ We're living in this culture in which everyone needs to meet you where you are, otherwise they don't love you. This process, this invitation that you extended—even choosing the technology to say, ‘He'll identify with this’—it feels to me like such a necessary reminder that the goal isn't always for someone else to communicate explicitly in the way I need them to. It's for us to meet each other at some point and decide where we go from there. And so I wanted to bring that up because I thought that gesture from you was just such a potent and poignant reminder for this moment we're inhabiting together now.

PHOEBE:

Thank you. I really appreciate that and how you've worded it because, yeah, you know, you get in the weeds, I think, when it's such a personal relationship. So thank you for saying that. Yeah, that means a lot to me, actually.

JOSH:

Over the course of my research for this conversation, I learned that the audiences within and beyond your work matter to you in an extraordinary way. And so I'm very curious—basically, this is a selfishly curious question: how do you manage the balance between your desire for creative expression as a way of understanding yourself in the world and the challenges that can arise when we present our art and indeed ourselves to the public?

PHOEBE:

The challenges being what?

JOSH:

Criticism. Misidentification... Maybe I'm shielding myself. Hold on, let me approach it this way. Busy Being Black, my writing and my poetry—my creative practice is often a way for me to reveal more of myself, not only to myself but to other people, in the hopes that I might be able to get closer to and more intimate with other people, to become more entangled and enmeshed. And that's a huge growth and shift away from even two years ago, right? This desire to be a bit more open. So the challenges for me are maybe public and private, right? There's the interior world and a voice that says, 'This is too private and you don't need to share this, and you look weak or like you can't handle life. You're a man', you know? And then also putting yourself out into the public space as an act of—as an invitation for others to also be vulnerable and intimate—sometimes it's denied, right, we're refused, or people aren't ready for it, or you're misunderstood or wounded sometimes. And so much of your work is asking people to come to you and to come participate in this external expression of your interior world. And so I wonder if any challenges emerge for you in that process of bringing Phoebe Boswell to play in community with other people via your artistic practice?

PHOEBE:

In many ways, I see myself as a conduit, and I often think about how my work can be of service to others, whether they're the people who come forward to be participants in it, or whether it's the audience that meets it. And because so much of my work is very multi-layered, I think it's really difficult for someone to have a very clear, one-minded view on the work, because it doesn't really allow you to do that. It asks that you look at it in multiple ways. There are usually multiple voices within it. It's not me telling you what to think or how to feel about something. I anticipate that people will have differing views on it—again, people meet it where they are, and I think that says more about them than the work.

I think if I worried too much about that, I'm already a huge overthinker. So I think I would struggle, and what I would struggle with is trusting that the people who are involved in the work with me will be held properly. I care more about that than being personally criticised, but I say that because the work is a way for me to—I feel like I can be braver in that than this. This kind of vulnerability I'm more nervous about. This gives me a lot more anxiety because it's me, and I welcome the invitation because I think that you do it really well—you meet people where they are. I don't know. You have to meet yourself over and over and over again when you're making anything, and you meet the bad sides of yourself and the good sides and everything in between. And so that's enough of a critique for me

JOSH:

Oh, I understand, yeah. Before our conversation started, we said, 'Let's speak from the scar, not from the wound', and this happens on Busy Being Black. Sometimes I'll ask a question, and I'll hear the response and I'll know that my question came from a wound. That reluctance to be fully myself in the public space and—you know, maybe one doesn't need to be their full selves in the public space. I rail against this idea of authenticity. I think it's so contrived. Whoever we choose to be in any space is us. It's a decision that we make. It's an armour that we put on and we fashion, we buff and we shine—it's ours. And so being able to discern in which moments and with which people it's safe to show up in different ways is a huge part of growth and indeed healing.

PHOEBE:

Safety is really key. I think we have to know the world that we live in and how it responds to us and our, as you say, authenticity. Art is a gift because it allows me to be vulnerable in a public place and for me it's more to do with how you feel safe in your own body, how you feel safe in the most intimate relationships and then how that kind of widens out; and it's a constant navigation of how much do I allow my fear to be dissuaded by this possibility of love or anything else—from first myself, then my intimate people, then the wider community and then the world. It's a constant navigation. I get it wrong often. I don't know if it's right or wrong about it, but I—yeah, it's not easy.

Poetry cannot be a replacement for therapy. I was literally misusing poetry: I would perform poetry on stage while my wounds were still open, and I got addicted to the praise. I need to have a safe distance between myself and my pain and the output of it.

BEN ELLIS

JOSH:

You're bringing to mind a conversation I had with a poet a number of years ago. One of the things that stood out to me was that if performing a piece of work still makes you cry or it still hurts, that it's too soon, that you should wait until it doesn't hurt before you share it. And at the time, I was like, 'Yes!' because it was permission for me to keep it all in: I'm just going to wait until this is baked, and then I'll share it. Your work is this intimate and global conversation about rupture and repair and enslavement and misogynoir. These are wounds that will hurt within you and within the community. So I wonder how that advice lands with you about waiting until the wound doesn't hurt.

PHOEBE:

I think it would be wonderful to assume the wound is going to stop hurting!

JOSH:

Touché!

PHOEBE:

I mean, when I feel really great, the last thing I want to be doing is making work. I want to be making love or going on holiday. I think we're very lucky as artists to have this place to be able to tend to the wound in a way that is not destructive, in a way that offers something to ourselves and then to whoever might then reach it. I think the wound is an enigmatic place to make from or to think from, and it's a messy place. I think the making can be made whenever you need to make, and usually I need to make when I'm feeling something really deeply in my belly. And the way you then speak about the work, perhaps it benefits from some time, so that you're not projecting onto it in a way that is not beneficial to you. As we were saying about the narratives that come with wounds, you sometimes become more stuck in the narrative than in the wound. And you don't realise the wound actually has scabbed over and healed, but you're still saying the same wounded narrative.

JOSH:

Lorca said that all great art has duende. He used flamenco dancers as the example par excellence: the guttural stomping and the clapping and the hoarse singing is the darkness of the interior scraping its way out. And that's how Lorca identified what was art or poetry as provocation, as opposed to propaganda.

PHOEBE:

We also have to contend with the fact that, as Black people, our trauma and our pain have been so heavily commodified, and so there's a kind of perversity in a way to always making that kind of work. I think sometimes you have to refuse to do that, and you refuse to only do work that is harrowing.

JOSH:

I think listeners can anticipate what's coming as well. Kevin Quashie told us: Blackness, as we understand it in the West, is anti-Black, right? Capital-B Blackness is always supposed to tell us something about democracy or progress or violence, and what we miss in that construction of Blackness is what he calls our 'wild and voluptuous interior worlds'. So, I think of that too, that refusal and indeed retreat—I'm actually going to retreat into my interior world, that is also an act of refusal, right?

PHOEBE:

And offering a place where we're not always thinking about that. And we're able to celebrate joy and, you know, all of these things that we have in abundance.

Phoebe Boswell, Love’s Promise to the Weather, 2024.

JOSH:

I think this leads us very beautifully to Like Hydrogen, Like Oxygen, which was presented at Ben Hunter Gallery in London. Phoebe, I gasped when I walked in. It literally took my breath away, and my best friend, Lerone, was there too, and he was like, 'Oh my God.' And I said, 'I told you: Phoebe Boswell.' We'll get into what specifically took my breath away. First, invite us into the genesis of Like Hydrogen, Like Oxygen.

PHOEBE:

So I've been thinking a lot about bodies of water since The Space Between Things, as these spaces that are remedial, they're healing, they're womb-like, but also they hold historical and contemporary migratory trauma for us, but also they are the places between here and there. So they could be the places of non-citizenship. And if we think of citizenship as always being aligned with unfreedom, because not all citizens are treated the same and citizenship in itself requires a kind of power structure that doesn't hold us all the same. So these spaces of the in-between can become kind of spaces where we can contemplate liberation. So I was doing a lot of research and a lot of work about bodies of water. I was the Whitechapel writer in residence in 2022, and they give it to artists to use writing in their work, not to writers. And it kind of pushes you to think about writing more clearly and more focused. So I wrote Bodies of Water, which was a performance piece. And I also made a piece called Dwelling for the Lyon Biennial, which was curated by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, and it was called Manifesto of Fragility.

In the process, I found out that 95 per cent of Black British adults don't swim. And I did lots of research in the residency about asking people about their relationships to water and to swimming, and it struck me that we need to reclaim the water. So I rented an underwater recording studio, an underwater tank. And I invited people to bring their loved ones and help each other feel safe in the water. Over two days, we gave each couple—I think between an hour and an hour and a half—to just do whatever they wanted to in the water. And we kind of left them to it. It wasn't guided at all. And we filmed it. And it became this choreography, this amazing choreography, which had in it like fear and courage and intimacy and holding and trust—it was like a ballet of all of these things that, like all the work that I do where I invite people in, these couples really brought to it such generosity and such courage. And I was really stunned by how everyone brought themselves to the work.

Phoebe Boswell, There Are Other Worlds, 2024. Installation view at Ben Hunter Gallery.

PHOEBE:

Years and years ago at art school, I was dissuaded from painting. All I wanted to do was be a painter, but I was dissuaded from painting by a white man tutor. I was painting my sister, and he was like, ‘I don't really get what you're trying to say. You should make her blacker.’ And I said, ‘But she's not blacker,’ and he said, ‘Yes, but if it was a portrait of a Black woman, I would know what you were saying. What I suggest you do is stop buying paint and instead spend your money on Miles Davis records and go and hang out in Brixton.’

JOSH:

Whoa.

PHOEBE:

And I was too young at the time to know how to critically fight back, and I was much less conscious at the time—I didn't grow up here, and I didn't grow up in a predominantly white place, so I didn't have the language at all to know what conversation I was actually having at the time. I just knew what he was saying was heinous, but it completely floored me, and it made me really paralysed. And I started to think that I was just very fraudulent because I couldn't fit what he understood to be Black Woman Art—I had nothing to say, and I stopped painting. I didn't paint again after that. I don't owe him anything, but I owe to that moment the fact that I then just spent my time gathering all of these different skills and languages and tools to then have a practice that is very multi-layered. And I'm grateful for not just pursuing painting solidly and going down the route that I thought I would, which was to be a portrait painter of oil paintings. I think I've had a very errant journey in my practice, and I'm glad about that, but something about seeing these people swimming in this pool and helping each other—I was like, ‘I need to reclaim paint.’

The reason I wanted to be an artist was because I love painting so much, and I stopped myself for 20 years. So I decided I'd paint from stills from this shoot that we did, and that's the work. And so this is my first painting show. It's my first show that doesn't have technology or doesn't have any—you know, like it doesn't have a lot of immersive stuff. It is the paintings, and that's what you're given. And yeah, that's what you saw.

JOSH:

I feel very emotional hearing that. Phoebe, I'm so sorry. And also, that is literally the definition of triumph. I was blown away. I wrote to you about it. The blue in Love's Promise to the Weather—I moaned with delight. It is a perfect painting, to my mind. I mean, all of them are, and it had never even crossed my mind that you hadn't been painting since school. And so to know that this—that this process, oh, I’m so emotional because we find ourselves in community, right? In this very process of you engaging with community and learning from them and observing them, you’re provoked to return to the original medium. Phoebe, that's just—it's tremendous. That makes me want to combust into a million pieces. Wow, Phoebe.

This is what I found so breathtaking and breathgiving in [Dionne] Brand’s Verso 55 in The Blue Clerk. The ancestors’ surprise, their utter delight that we who were never meant to survive, ‘are still alive, like hydrogen, like oxygen’.

Christina Sharpe

PHOEBE:

It's a very meaningful show for me. And the other thing about that painting, Love's Promise to the Weather—and the reason why I was… not hesitant about doing this, but when I read what we were going to be talking about, I was … it gave me a little pause because in August 2024, my heart gave way again, and I was in the hospital, and it was very alarming, obviously, and a lot came up from the narrative of the previous time. And then we had to decide whether to do this show.

I was very weak, and the doctor was like, ‘Please don't do it. Don't do anything for six weeks.’ But I came home, and it was a similar feeling of I need to get to the studio or else the old narrative is going to take hold, and so I went to the studio. I could only do anything for about 10 minutes, and I had to lie down and I had to get up again for 10 minutes, and lie down. Love’s Promise to the Weather was not finished, so the first thing I did was finish it—and it wasn't blue before. And it was such a joyous thing, and it just came in such a real way and with no hesitation.

So I love that you love that one because that was the one that brought me back to myself again after this next heart thing. I'm reflecting on the first question you asked—how is your heart?— and it's strange to think about it because it's tested me so much, and in many ways it's fragile. I know now because of what's happened to it, it's going to be fragile forever. But at the same time, paradoxically, it's absolutely not. For me, that's what I see in this show: your heart can do miraculous things.

*

Busy Being Black transcripts are edited for clarity and readability.

Rehumanising the Black Meme

Legacy Russell is a curator and writer who shows how Black people have shaped viral culture, revealing the economies of extraction that predate the internet and pointing towards collective world-building.

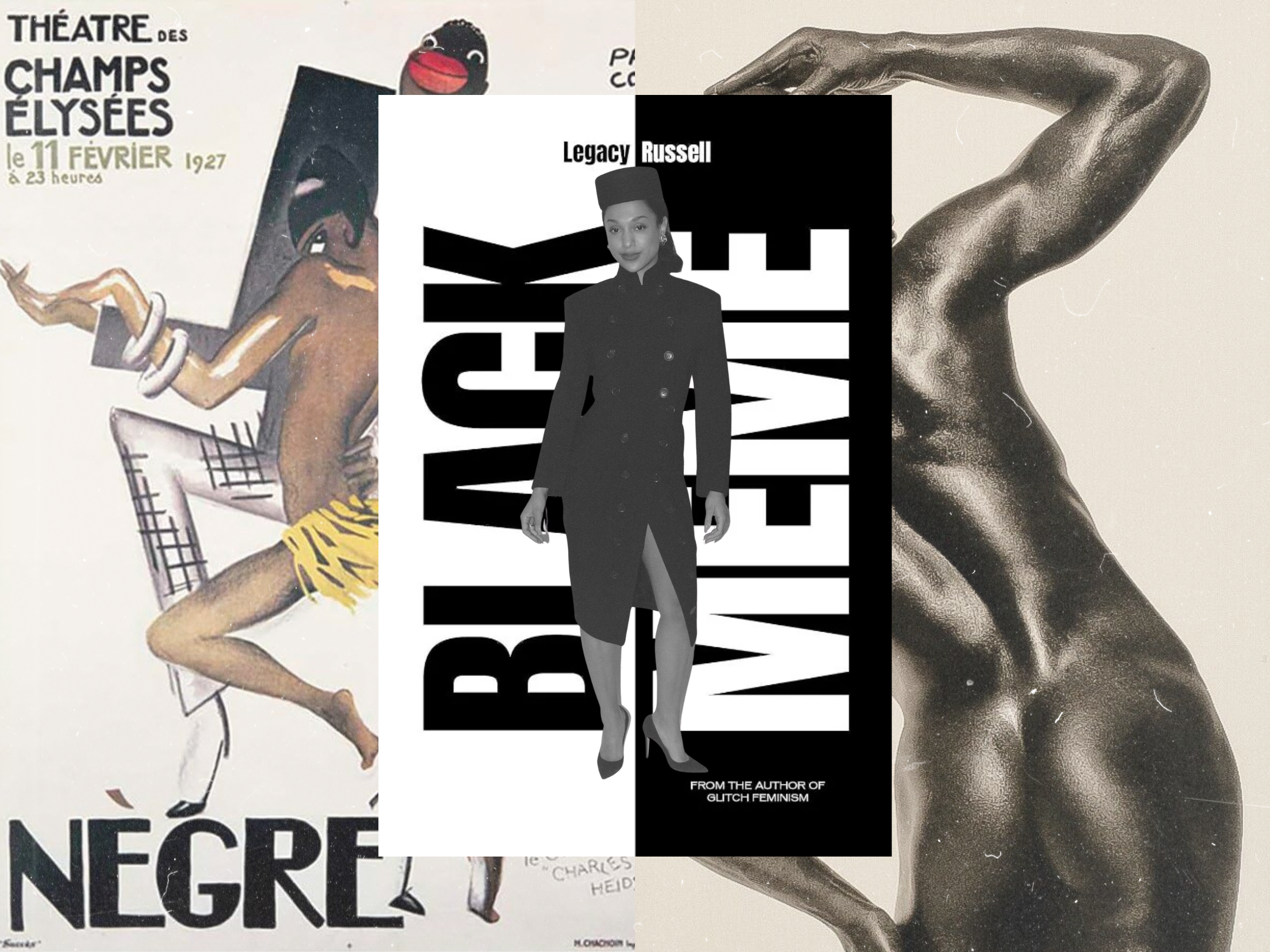

Au Bal Nègre poster (1927), Herb Ritts photograph of Djimon Hounsou (1989), Legacy Russell's Black Meme (2024) and Deirdre Lewis photograph of Legacy Russell for Interview (2024).

‘The very idea that lynching postcards would become memorabilia means that there is still an economy around these materials. They would be kept and maintained and preserved, not necessarily always as a document of their violence, but often as other types of documents of correspondence or communication of intimacies that travelled across state and international lines: this was viral culture’.

LEGACY RUSSELL

INTRODUCTION

I've been invigorated by Legacy Russell's ongoing inquiries into how we come alive together. Whether she's encouraging us to think expansively about the connection between marine life and Black agency under duress, or pointing us towards the liberatory possibilities at the intersection of our bodies, genders and technologies, her work is evidence of her desire and drive to live in a world in which Black folks thrive. In our conversation, we explore the role Black people and our images have played, often against our will, in shaping the modern world; our responsibility as global and digital citizens to harness the internet to collectively push forward a generative vision of the future; and what we learn about Black self-determination from the ancestors who refused to survive the Middle Passage.

Legacy is the Executive Director and Chief Curator of The Kitchen, and her latest book Black Meme traces how viral culture and networked communication predate the internet altogether. From lynching postcards that travelled internationally in the early 1900s to the commodification of Black death on Getty Images today, she reveals how anti-Blackness has always operated through image circulation and economic extraction. But Black people are never only the worst thing done to us, and Legacy offers grief as a form of critical analysis that complements the essential effort of truth-telling at the core of her curatorial practice. It is only by aspiring to the truth, she says, that we can open up space for the imaginative world-building of our artists.

Black Meme with Legacy Russell is available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Josh:

Legacy Russell, I am so supremely honoured to be in conversation with you. Thank you so much for accepting this invitation.

Legacy:

I'm so grateful to be here and just really honoured to have the opportunity to just, I don't know, chop it up on a Friday.

Josh:

For listeners, Legacy and I first met back in 2014, and it feels really wonderful to be back in each other's orbit. To open all of my conversations on Busy Being Black, I ask my guests the same question: How's your heart?

Legacy:

My heart today is whole and full, and I think with some grief. There's a lot that's happening in the world, and as we continue to follow on and prepare for these months ahead, there is always this tinge of grief, recognition and awareness. But I'm trying to sit with it and be mindful today.

Josh:

Looking into the scope and the body of your work and the particular intersections that you focus on, you really don't shy away from grief. And I would love for you to talk about how grief shows up for you in the work, or rather why it's so important to hold onto it so gently and so rigorously.

Legacy:

I think that grief can be instructive, right? Grief is one of the most profound articulations of love, and I aim to think deeply about what it means to have empathy inside of my creative and curatorial work, my academic practice, in terms of my writing and research—that's really critical. Often when we think about art history and the ways in which folks are remembered within our history, there is an assumption that our emotional self or somatic self is intended to be set apart. And I just believe that in this moment of visual culture, that needs to be redressed, that having a more integrated sense of self and also recognition, too, of those tender moments is part of the radical vulnerability that scholarship needs now.

Josh:

I had a conversation with Elijah McKinnon, who leads OTV, and they really blew my mind when they told me the difference between vulnerability and transparency. And that provocation that Elijah offers—that transparency is actually quite easy, but that move towards inhabiting vulnerability is a much more difficult endeavour, but much more generative as a result.

Legacy:

Being vulnerable means that you are truly allowing other people to see you, right? And also creating space for other people to be seen. It is definitely a great provocation to think about that relationship to transparency. I think some of the ways that transparency has often been bureaucratised are with this assumption that everything is seen, but in fact transparency is its own strategy of opacity and sometimes, actually, can do the opposite work. So I love that. It's an interesting call into presence, for sure, as we start this conversation.

Josh:

I'd love you to take me back. How would you begin to talk about your first encounter with art as an awakening experience for you?

Legacy:

I grew up in a household where we didn't have a lot. I grew up in one room, in a studio apartment. My father moved from Harlem to downtown, and my mother had moved from Hawaii and was living in the East Village when they met. This was in the 1970s, and the rest is history, as they say. But I mention this because art was everywhere because I was in New York, right? And what an amazing thing to be a kid in New York. I appreciate that my home was filled with books and I had an amazing and enriching community, in terms of a kind of downtown milieu. My parents were very rigorous in taking me to all sorts of places. I grew up in the kind of downtown scene where there was this relationship between institutional space that was not inside of institutions. So literally in the church, in the bar, in the park, and then thinking very much so about the ways in which creative space would travel from sites beyond institutions into institutional sites, like museums. I was always going between these different types of institutional presences. And I also learned, too, that individuals can be institutions because, especially in a city like New York, I grew up with some deep understandings of such a rich history of performance and how the radical avant garde shaped what that vision looked like, with Black and queer people at the forefront of that.

Running alongside of that, I will say that it was a bittersweet thing being in that moment of growing up in New York in the eighties and nineties, and really what occurred of the mass erasure of so many different types of creative spaces, small spaces and also institutions, as in individuals, right? Because the eighties and nineties were a period of time where folks who had moved through different models of gentrification and city change we're in and at risk of being extracted from, and then also moved away from the core parts of New York City. To be a creative person in that period and to make a decision to be inside of a creative community was a political decision in addition to an artistic one.

And so for me, I think that was really formative to learn as a lesson early on and then to be able to move between different institutional spaces and deepen in my understanding of what it meant to really feel entitled to be in those spaces, even though I had not come from them. Those were some of my early memories, and it was wonderful to think about, in my life trajectory, that some of the earliest institutions that I had spent time in were the Studio Museum in Harlem, which I now have had the immense pleasure of being a curator inside of, and then, of course, The Kitchen as well. So these are organisations that were part of my bedrock, and I still feel very grateful. My parents do not walk this earth now, but they are, of course, in the presence of some of the ways in which my life has taken its course.

Josh:

Your response opens up that period of time when we first came into each other's orbit, and around that time that I was at Second Home, we hosted that round table dinner with The Serpentine about the role of public art and sculpture, and my mentor, Eric Collins, was there, and it was him who was really quantum leaping my understanding of what I love about art and who really challenged me to ask more provocative questions about the role of Black artists and Black art, which I think is a kind of never-ending, open-ended question...

Legacy:

Always—and a deep and profound question. The questions of public space are really important, right? Who does it belong to? And one of the things that I think is really interesting about public art is that it is a private movement that moves through public space, right? Because someone has to pay for public art as it lives in public space, and oftentimes, that reveals how privatised funds are moving through a space that folks feel they are sharing as a commons. So within this, I think it's a really important history, because when we think about what it means to have folks occupy space and to be inside of public space or to create new models of privacy inside of public space, be it online or out in the world in physical space, this also too is part of a Black strategy. It's something that's really amazing. Blackness instructs us towards where those enclosures can occur and how those kinds of rips and tears and fissures can be generative and productive and exciting and rigorous.

Josh:

There's a full circle moment here as well, because you're also speaking with experience of walking public streets with access to art that was genuinely, truly public and that didn't require the kind of machinations of the private industry behind it to make it capital-A art, as we understand it, right?

Legacy:

I definitely feel like the principles of that were really instructive and important [and feed into my work] at The Kitchen, which, of course, is an institution that has created an entire history of thinking about this idea of experimentalism in relationship to the ‘avant-garde’—and I put that in quotes because it's a history of failures of belonging, in addition to the moments where folks have felt engaged and included. And when I say ‘failures of belonging’, it's because I think there have been a wide number of discussions around the avant-garde and what that means as an identity, as a brand, as a reputation, institutionally or otherwise, but what we know is that so much of the avant-garde was not intended to live nor survive inside of institutional space, right?

Black folks, queer folks and historically oppressed folks have contributed to the avant-garde and really shaped its very possibility to sustain itself to this moment now. Projects like Just Above Midtown and Linda Goode Bryant's contributions there of creating a space for Black folks in a critical moment where institutions were not showing up to do that work here in New York City, that these were histories that ran concurrent to organisations like The Kitchen. And with that, I think it's a really important set of questions about what the diaspora of the avant-garde is and who is able to take on or claim public space and why, of course, it is so tender and monumental to think about the ways in which Black folks have changed our very understanding—not only a visual culture and representation, but really how we are intended to exist in public and to live, which is the great hope.

Josh:

You're making me think about the sense of entitlement I've taught myself to have in institutional spaces. I remember in 2017 going to the National Portrait Gallery at Trafalgar Square. And as I was walking around the building, it occurred to me that this building was probably built with money earned from the Transatlantic Slave Trade, right? And then we were having a conversation up at the restaurant at the top and looking out across London's iconic landscape, and I was like, ‘Oh, all of these buildings will have some sort of connection to the blood of my ancestors and our diasporic history. I belong here. Whether or not I'm on these walls, I'm in these walls’.

Legacy:

Exactly. The question of belonging is really important, and the question of entitlement. I love that word as you brought us back to it, because I often use it. I do think folks should feel entitled to be inside of institutional spaces and entitled to understand the many spaces and passageways between them, in terms of folks having to find ways to innovate in the face of being closed out of institutional space. It's also part of the work to push further what culture should look like. I also believe deeply that, with all that has been generated by the fungibility of Blackness—that we have been an economy in and of ourselves, that we have been machinic and put to work in our labouring; and then we have been extracted and borrowed from, and recited and cited a thousand times over, both with and without credit and often without credit—finding ways to take back and reclaim space and to think through what authorship and conviviality can look like as we share space is a really important mission. Even just being in conversation in this way does some of that work because these are the intimacies that we need across Black people.

Josh:

Listeners can't see me, but I'm blushing.

Legacy:

I believe it deeply. I'm blushing, too. To even sit with you, it’s such a special thing.

Josh:

Thank you for saying that. So, I have Black Meme here.

Legacy:

I've got it too. It makes my heart whole that you have it in your hands.

Josh:

Well, I tagged you in a million Stories because this is exactly the type of book—I feel like Oprah right now! ‘You need this book!’—but this is exactly the type of learning that I love to do. There are so many provocations in this book, and I had to choose somewhere to begin. So we won't get a chance to cover as much as I want to, and I'm encouraging listeners to get their copy of Black Meme. The first thing I want to ask, though, is when did you start thinking about what would become Black Meme?

Legacy:

This has been a kind of wild and crazy ride of research for years now. And for those who know me, I'm always collecting little bits like a magpie and thinking about the ways in which I'm seeing certain things in the world and saying, ‘Maybe actually this is an image that I need to be writing about,’ or I'm following a line or a thread about an artist who is doing really inspiring work. And so I have lots of wild Dropbox folders. My desktop is a mess. Too many tabs open. I think that the research for Black Meme was initiated by bringing together an amalgam of images and beginning to look at them and study them. And many of them have made it into the book. And we had to think deeply about what it meant to make some selections that would carry us across space and time from 1900 to the present day. But then, at the same time, some of the early thinking around it actually came in the form of a video that I made. Language is my first love, so I'm always writing and reading, but I also produce video works. And this is something that folks who have followed my work with Glitch Feminism may have seen as well.

So I created this initial video and then began to do some lectures—and then the [Covid-19] pandemic hit. So it was a really interesting period of time because within those early months, I had just decided this has to be a book, and I think that this is something that I need to be investing space and time in, but of course, who would have imagined that stepping into formalising it, taking it out of the lecture space purely, and then having it become something that will become a material that people can hold in their hands would begin within a global catastrophe?

Josh:

And a global catastrophe that coincided with, or collided with, or combusted with the historic and ongoing pandemic of anti-Black police violence, right?

Legacy:

That's right, and I think it's interesting because one of my first lectures around this was for the Atlanta Contemporary in the middle of the pandemic, and we were on Zoom, and it was a really deep and touching moment because the things that were, as you said, combusting all around this. And the discussion that occurred afterwards was incredibly impactful and transformative. As often happens with different types of scholarship, you wonder what place it will have in the world. You wonder often, when you are an author of any type of text, if you're taking it piece by piece and year by year, if it will be relevant at all when you complete it, right? These are some of the questions that I think creative folks are very familiar with. And the thing that was profound and devastating was that from 2020 to this May, when the book came into the world, the deepening of these discussions only became more urgent. One would hope actually that there would be no need for this book, but within the context that we have been in, and with the acceleration as well of images as they move and images as well of Black people, it becomes an incredibly important nexus to stand on and to think through how we create space to have this be a slow read of a fast topic.

Josh:

So, you're magpieing different ideas, images and themes; you're starting to weave them together ahead of the pandemic and ahead of the collision of Covid-19 and the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, among many thousands of others. Was there something that you had a hunch about that was confirmed for you in that collision?

Legacy:

I often say about that period of time that we went in that moment from almost 1990 to the present day within two months, in terms of the ways people romanticised and revisited different moments of the birth of cyberspace as we now know it. And then as well, how that all fell apart, right? We can remember that in the March and April period, everyone was sharing reading lists and talking about collectivising and reclaiming space and baking bread and doing all the things. They were banging the pots for their essential workers. Showing up for those who do the really unflagging, tireless and devoted work of caring for others. Those moments were so defining for so many people in all different corners of the world.

And then, of course, within that all the digital discourse, how folks were learning together inside of Zooms and having conversations and organising that would travel through and beyond our screens. And, by the time that we hit September, there were so many moments of that that had fallen apart or that folks felt disillusioned about and deeply alienated about because of the immensity and, as I mentioned before, the acceleration of social media. So much violence, as well. So many failures of the systems of care for folks during a period where so much was in a global collapse. All of that was set into the context of thinking around how this could come into being.

And for me, it was really important to also think through some of the questions as to why a book like this even exists. A book like this is intended to instruct us that images always live inside of other images and that we don't get the chance to divorce one image from another because, in fact, when we are looking and reading our world actively, we are seeing a thousand images that have been produced before, whether we are aware of it or not. And so some of our responsibility as citizens in this moment, as global citizens, is to think about the fact that every image has another image inside of it. And every image of Blackness is also bound up with the carrying of so many other images of Black people. And so the responsibility of that is huge.

When I'm inside classrooms or when I'm giving lectures, people often place a lot of blame on digital space, right? Folks will say, “Oh, it's because of the Internet that these things are happening, and that's the thing that needs to be fixed or solved.” But the accountability lives with human beings, and the reality is that regardless of whether we are inside of digital space or not, the existence of being on the internet is an integrated existence. And so that would be the great hope—that folks have a level of accountability and awareness about what is being engaged on their screens in a way that they would carry out into the world. Which then drives the thesis: perhaps some of these core questions, which are addressed in the book, predate the internet altogether.

And that was my sneaking suspicion, as you had said. The hypothesis was that perhaps aspects of how we think about networked life and models of communication and image exchange exist in ways that have nothing to do with the screen as we define it now, but every screen that came before; and then, as well, has been informed and influenced by technologies that have allowed for us to view and exchange these images and that Black folks have been at the centre of it all.

So, I said, ‘Let me get started and take a look’—and lo and behold, what is evidenced within this research is that we can see that from the very beginning of media and scholarship as we have shaped it around media, that these changes have been prevalent and that the acceleration of it has been driven by individuals, but also at the same time [media and visual culture] has been uplifted and upheld by the contributions of Black people.

Josh:

When you flipped the lynching postcards into the legacy of Black memes, I was stunned, and so when you brought up that people blame it on the internet, on the technologies, the book refutes that position, right? Actually, look at the way that these lynching postcards travelled internationally, as you show in Black Meme, and the joy and revelry associated with that international travel: ‘Look where I was. Look how I'm documenting my life and aliveness as a white person, in contrast to Black death’.

Legacy:

And also how these things are kept, right? The very idea that lynching postcards would become memorabilia means that there is still an economy around these materials. They would be kept and maintained and preserved, not necessarily always as a document of their violence, but often as other types of documents of correspondence or communication of intimacies that travelled across state and international lines: this was viral culture. And so when we ask questions about speed and we say that the speed of viral culture is solely defined by digital space, it's important to look at how that has come into being and the ways we can think differently about our integrity and participation within that, in this moment now and as it has been set forward by the generations before.

Josh:

And I think another helpful offering here is also the fact that you can still purchase lynching postcards on Getty Images, and you list out the image sizes and the associated costs to buy these images of Black death that happened, as non-Black people like to tell us, ‘All that time ago’, right? ‘Let it go’. But yet, here it is. It's still commodified. It's still purchasable. It's still enabled as memorabilia. It cannot be divorced from that violence, right?

Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, lynched 7 August 1930, Marion, Indiana. Photographed by Lawrence Beitler, commercialised by Getty Images. [Image modified out of respect.]

Legacy:

And I think the ongoing discourse around how these economies still function, as if they are separate in their economies from some of the ways in which we can think about what it means to acknowledge and dialogue around what is due to Black people, I think is a really important conversation. And it's sticky and it's hard, and it doesn't have a simple solution, but I believe that it's a really important thing to see the connectivity between those two dots and also to be able to understand that when we talk about digital media and the way images travel, these are conversations about the histories of an empowered economy or a dispossessed economy, and who is on either side of that comes with race, gender and class lines.

Josh:

I hope you won't mind me reading a passage for listeners; it's from my favourite chapter.

Legacy:

Oh, please do.

Josh:

I would just say that it sounds odd to say that my favourite chapter in Black Meme is ‘Eating the Other’, but we'll get into why. Okay. This is on page 43, and I want to read this because I really think it drives home this point.

‘[There is an open] source model that drives what social scientist Kwame Holmes expands on as a form of “necrocapitalism”—an extension of political theorist Achille Mbembe's necropolitics—that makes “the value of black death” a fungible commodity, worthy of exchange. Holmes cites the rise in “home prices in the St. Paul suburb of Falcon Heights... at an impressive clip of 13%” in the wake of the murder of Philando Castile by officer Jeronimo Yanez, live-streamed by Castile's partner, Diamond Reynolds, calling it “the area's most robust bull market since the subprime speculative bubble.”’ (p.43, ‘Eating the Other’, Black Meme)

Legacy:

It's outrageous, right? And it's distressing. I had an early lecture with some students, and there was a student who got up and said, ‘What happened to you that made you want to write this?’ And I said, ‘Being born’. What an interesting question to come from a young person who is a non-Black person, because the very assumption, first of all, that something would have had to occur, as in a singular event, to be accountable to this history. And then also the very assumption that this is a Black issue: if I'm not a Black person, I don't have to care about this. These are the things that are very flawed in the logic that Black work is the ‘Black stuff’ that folks set apart and study.

These are the spaces that instruct the entire world towards models of liberation and change. We have seen that time and time again. And what it means to be able to take seriously that if this is happening here, that its implications are far and wide, and that it sets a standard and a blueprint for the ways this can happen to all sorts of people—and has continued to happen to all sorts of people in terms of histories of dispossession that are shared across the world. So the economies of it are deep, and when we make it a superficial issue, that it is about the entertainment purely, that it has nothing to do with economy and that the rigour of the discourse around the economics is something that we are not responsible for, we are really fooling ourselves and selling ourselves short because it's far more rich and interesting and far more devastating and nuanced than what often folks perceive.

Josh:

Part of my anger is that I did not know this information that Zimmerman was auctioning off the weapon that killed Trayvon Martin or that the murder of Philando Castile made a previously unattractive area attractive. I shouldn't be so surprised by that. I shouldn't be so devastated by that.

Legacy:

It is devastating. And Josh, I really hold you in that. I get chicken skin talking about this because it is infuriating and it brings me so much grief that it can be hard to articulate because really what it shows is that what it means to feel safe in one's neighbourhood is predicated on supremacy. And that is an incredibly dangerous proposition, but actually it is an age-old one, and it is not new. So when we convince ourselves that in this modern world everything is new and that it is set apart and we have evolved, we give ourselves permission to distance ourselves from what really are these very mediaeval tactics. The kind of currency of exchange that is established by how economies resonate through these acts of violence is a really important thing to be reflecting on and to feel upset about—and to understand that the work is not to have the feeling stop there, but to move ourselves towards action and empowerment to better understand [how we bring about a] future of a world where Black people are truly loved.

Josh:

And this is why regular listeners will hear me talking ad absurdum about grief and mourning. I had a conversation with Dagmawi Woubshet about the tremendous courage and bravery of public mourning rituals during the AIDS crisis, or during what Jafari Allen calls ‘the long 1980s’. I've got Assotto Saint's newly-released Collected Works here too. And there’s this idea that grief can not only be metabolised but that we grow around our grief: we become bigger in grief because we learn to accommodate that loss. At a time when their lives were on the line, these black creatives and writers and thinkers and movers and shakers decided to write through the storm anyway, to show up and they did it so intentionally, right? Was it Melvin Dixon who said he would be listening out for his name? And so I think that this anger that emerges is an old anger, right? It's not just mine.

I come to you bearing witness to a broken heart; I come to you bearing witness to a broken body—but a witness to an unbroken spirit. Perhaps it is only to you that such witness can be brought and its jagged edges softened a bit and made meaningful.

MELVIN DIXON

Legacy:

Absolutely. There have been moments in conversation with folks across these many years, with pandemics and other things as they continue to occur in the world, where folks are in debate, right? What is the catalyst that really can come of rage? Is rage productive? If I feel this feeling, is it something that breaks things, or rather, does it make something new? And I think it's possible to be an immensely joyful, immensely optimistic and immensely hopeful person and still have a connectivity to the fact that there are these things that make us feel so wounded and so disappointed.

And at the same time, to have moments where that can come in the form of anger. These are motivating points, and the thing that is amazing about grief is that it has so much inside of it: the loss, the loneliness, the love, the anger and the hope, right? Grief is a hopeful emotion. It establishes forward what we would hope to resolve. And so that feeling of absence and presence living at the same time, I think, is one that, as human beings, we really struggle with, and that we as Black people are not provided the opportunity to synthesise effectively. God forbid that we admit that grief is an emotion that we share, nor when that emotion is rage. But rage is a natural human condition.

The question just becomes, what do you do with it? And how do you move from a place where that can be paralysis, where you're held without being able to consider what lies beyond it, to a horizon where you can invest in making something new and building something that can be productive and imbued with love? I think both things can be possible. And that's why it's really complicated. So often Black folks are asked to live through one reality and try to set apart another when that ask is actually not made of other folks, in terms of an equal ask for folks to be disassociated with some of those core emotions.

Josh:

This might be a stretch, so feel free to don't rein me in.

Legacy:

Stretch!

Josh:

I have Dionysus on my bicep, and on my neck I have one of the cats that the Maenads were carrying. He's my favourite of the Greek gods. So for those who don't know, Dionysus was a demigod; Zeus's wife was jealous and sent the Titans to rip him to shreds. Zeus took Dionysus's heart and sewed it into his thigh. When Dionysus was reborn, he was like, ‘Fuck this’, and he escaped into the forest, into the sea, and into the woods, where he became the god of Bacchanalia, orgies, revelry, etc. But is it not grief that motivated his journey into the world? That made him leave home? And in that joy-making, in that ecstasy, he created the world that he wanted to inhabit.

Legacy:

Yeah, and truly feel through it, right? I think it's really hard to be a sentient being. To think about, as you said, what it means to travel from a place of injury to a place where you're thinking and feeling at the same time, and that can feel really empowering. It's also scary, right? Because again, if the lesson is that our feelings are different, pathological, that there is something wrong with moments where we recognise that sort of transfer of emotions, then, of course, we're going to program ourselves to react and think differently as a protective mechanism. So the work too is to think about, What are we entitled to? How do we create space that can be decadent and abundant and joyful, even inside of a moment where there are so many continued failures and so much more work to be done?

Josh:

I'm picturing both of us skipping among destructed buildings with a hammer, right? Joyful. [Laughter]

Legacy:

[Laughter] The dismantled house. Yes, for sure.

Long before the poignant questions of the color line and the Negro problem registered in the black imagination, it seems that a more pressing problematic confronted the black citizen: how does it feel to be an energy source and foodstuff, to be consumed on the levels of body, sex, psyche, and soul?

VINCENT WOODARD

Josh:

So, I said that my favourite chapter in Black Meme is ‘Eating the Other’. I've been yelling loudly that people should be reading Vincent Woodard's The Delectable Negro since I read it a couple of years ago. I can't remember that I've read something so singularly affirming—to be able to finally name the looks I've received, the violence I've experienced, the cannibal horror that I have felt subjected to, and that I know men like me have been subjected to. And I've been telling people, ‘Oh my gosh, they were actually cannibals!’ So I was thrilled—again, that sounds quite morbid—but thrilled to see you reference Vincent Woodward in this chapter, ‘Eating the Other’. What is the connection?

Legacy:

The work of talking about cannibalism within a visual culture is to push us further to think about cannibalism as more than just a metaphor, that we are active in those modes of consumption and how they occur. And the history runs deep and wide, right? It’s in the spiritualism and fetishism of Black people [white people], and that whiteness actually needs to consume to sustain itself. Is something that has happened both literally and figuratively as it has mapped out into the world, right?

So it lives together within a discussion of Black Meme and the ways folks have consumed Black culture, decorated themselves with Blackness, and created a souvenir of Blackness. This, too, is really critical and helps us think differently about some of the ways that we maybe have felt extracted from or consumed—and that it is literal. We’re kept from being able to really feel and acknowledge and recognise that, but Woodard's text does the work of showing us that this is not something that lives in the sky as a hypothetical, that it lives in an embodied self, and that we have seen it time and time again.

Black Meme takes that into the readership of images, but also this question of decoration, which is really critical: folks are donning trappings of Blackness, as if it is something that they are entitled to. The very idea is that Blackness itself is something that is meant to be worn. And so folks can wear that skin without any assumption that they're wearing it is a flawed logic. I really believe deeply that the text itself is all wrapped up in these conversations of how images travel and then also how we are eaten through those images.

Josh:

I've scribbled down Afropessimism on my notepad. I read a book recently that I don't have proximate to me, so I can't remember the name of the author, but it's in this book that I learned Afropessimism is not pessimistic about Black and Afro-diasporic people: Afropessimism is pessimistic about whiteness. Afropessimism gets quite a bad rap, right? People have a lot of critiques to lob at it, but I actually think there's a great deal of hopefulness found in Afropessimistic ways of engaging with the truth and engaging with reality because what else becomes possible when we take as fact that at the core of everything is anti-Blackness? I just wanted to start there and invite you to talk about what Afropessimism means for you and your work and how you think about the future.

Legacy:

For those who are keen to learn more about Afropessimism, there's a great book by Frank Wilderson. It's a dense text. You should give yourself a lot of time. It's not a beach read. So, you're going to be in there with all the citations and the notes and things underlined. But I will say that the way that this relates to Black Meme is to be thinking about anti-Blackness and the way that it can be analysed within a broader frame. As you noted, anti-Blackness exists at the centre of so much, and when we are reading anti-Blackness, that actually it is not purely a read through the lens of Black people but also seeing how anti-Blackness has created a blueprint and strategy for oppression across many global points.

You can find Afropessimism by Frank B. Wilderson III and Darkening Blackness by Norman Ajari in Busy Being Black’s Bookshop.

Josh:

And the book I was talking about is Norman Ajari's Darkening Blackness, and so for those who would like a softer entry into Afropessimism, that would also be a really great place for you to begin as well. So I'll include a link to both of those books, alongside Black Meme and Glitch Feminism, in the show notes.

You gave a wonderful sermon at Loophole of Retreat in Venice a few years ago, and a few phrases stuck out to me that I want to call you into as we close our conversation. The first is ‘the imagination of abundance’. And this feels particularly important within not only the context of this conversation and Black Meme, but the context of the loophole of retreat and the sermon you gave. I would love to invite you to talk about how you're rethinking the Middle Passage as a site of abundance.

Legacy:

To the point of Afropessimism, to take that thread and travel through your beautiful question, one of the strategies within the travel of the Middle Passage, forced travel of Black people as fungible assets, was to end one's life. And many folks have a hard time talking about this, right? Because I think it is a devastating part of a devastating history. But the strategy around ending one's life—folks who chose to throw themselves overboard—and what rose up around that—that in fact, there was a marine culture that was cultivated by those who were either forcibly thrown overboard or threw themselves overboard, right? Black people were sustaining a whole other ecology simply within the movement between different spaces and geographic points.

To talk about the radical work of what that meant, to make a decision to not see the other side and to be on one's own terms inside of a model of liberation is a devastating set of assumptions, right? But moves through an Afropessimist lens to think about what it means to be inside of an enclosure where one is able to dictate for themselves, with self-determination, how their lives should live—or not. Within this, I would hope for a different set of decisions for Black people into the future, but I also recognise that in itself, it is an early example of how quite literally different ecosystems have been sustained by the violence of supremacy.

And the kind of counterposition to that is to think, What does it mean to be able to truly live? And what does liberation look like? And how can folks maybe think about the strategies around that so that there is protection around our lives—in the policy of it, in the community of it, in the city planning of it, in the structural infrastructure and structural questions around it—and that these are also really urgent parts of the solution? It actually has to be seen in 360. It lives at every rhizome. It is something that exists in every part of our society, has to be taken into account and sometimes feels bigger than all of us.

How can we feel empowered when these things continue to happen? And it feels as if they are happening to us without a choice. The lessons of the Middle Passage show us that there's always a choice, and that makes me want to cry, quite frankly, because the choice may be limited, but there's always a choice. And so every day, when we commit to doing this work and thinking about what it means to uplift and uphold Black people and to truly love us, and then to not only love but to sustain us, that is a different type of choice. And that is a choice that is not just a Black choice.

Josh:

It brings to mind Cecilio M. Cooper's work on the Black Chthonic. They write, ‘[The wholesale positivist reclamation of Blackness as holiness]... obscures and squanders the insurrectionary potential of embracing Blackness’ cosmological alignment with the fallen, infernal and subterrestrial’. It also makes me think of Wangechi Mutu, right?

Legacy:

Exactly that.

Josh:

And how utterly exhilarated I felt looking at the hooved, horned, biped at the Afrofuturist exhibition at the Hayward Gallery a couple years ago. What is our allegiance to the human form?!

Legacy:

That’s right—and it's cyborgian. And I also think some of what Wangechi's work shows us is that we have always been a mutation and have been technological in our very form, and to think about how we can choose, with self-determination and care and an eye on liberation, how we want to be perceived and presented. And also in our perception of monstrousness, right? Because really some of this, too, is how we are surveyed as monsters and cyborgs; within that is an opportunity. And so this idea of even being seen or represented, and the truth of that, can be a very Black subject that can be defined by very Black means. And of course, artists always do the work of being able to instruct us towards how that can be viewed not as a hypothetical imagination but as something that lives on earth right here, right now.

Wangechi Mutu, The screamer island dreamer, 2014.

Josh:

To close our conversation, I want to ask you one final question. I believe, from hard-earned experience, that the creative process and the effort to live fully require the same approach. I've learned a lot from writers about the importance of destroying things to make way for new things, from painters who can often employ beauty to help us reckon with horrifying truths, and from musicians and poets who call us into a deeper relationship with our desires. What can we learn from the creativity and rigour required for a robust and enlivening curatorial practice?

Legacy:

What a great question. I think it's about telling the truth. That seems like a simple thing to say, right? But I believe deeply that we need a future of institutions that are prepared to tell the truth. And artists are incredible and have always been incredible because they show us not only that there is a future and many truths, but they bring us into impactful truths, just as you said, across disciplines that change how we see. The work of a curator is not only to care, but to tell the truth and to identify what that means [for our ability] to create space for artists where truth is part of the work of reconciliation and liberation, and truth is part of the work of creating space where people can really see themselves and feel through a wide variety of organisational structures, creative or otherwise, with the support that they need.

I think it's really hard as a curator to tell the truth because we are in a moment where truth itself is being questioned every day. We're seeing models of fact and fiction blurred and extracted from in all sorts of ways, as it is manipulated as a political tool. So it has always been a complicated thing to understand how to define truth. But curators are not just stewards of an art history that has already been written. It's about examining what's been written and asking who lives there and who has been shut out of that house. And also thinking differently about the ways some of the unwinding of the work is about acknowledging that maybe some of the things that have been told, said aloud, or perhaps ignored altogether have been part of shaping our understanding of visual culture and truth.

Josh:

Legacy. Thank you so much for this wonderful conversation. I adore you.

Legacy:

Adore. Thank you so much for having me.

*

Busy Being Black transcripts are edited for clarity and readability.

The imaginative work of becoming undone

Legacy Russell is a curator and writer who shows how Black people have shaped viral culture, revealing the economies of extraction that predate the internet and pointing towards collective world-building.

Photograph of Elijah McKinnon by DeLovie Kwagala.

‘The reason why I guard my softness is because I have experienced so much debilitating sorrow in my life that those parts of me are always healing. They are always in conversation with what I am experiencing in my world around me. And so in order to just humanise this hardness that I have had to endure and the resilience that I have had to embody, it is imperative that I allow myself the opportunity to experience softness and care and nourishment in a way that really informs and activates parts of my body here on this plane, on earth, right now.

ELIJAH MCKINNON

INTRODUCTION

Questioning and then breaching our limits is a salient and consequential concern—and a quest Elijah McKinnon undertakes as founder and executive diva of Open Television (OTV), a platform and media incubator for intersectional storytelling. Elijah’s insights into how their imagination is supported and encouraged by their pragmatism made me think and reflect on how I engage with my own, and we wax lyrical on a shared desire to become undone.